Impact: Rembrandt

The Apostle Paul, by Rembrandt

- Synopsis

- Introduction

- Life

- Christian Influences

- Paul and Rembrandt

- Self-Portraits

- Bibliography

- Links

Synopsis: A Painter and a Preacher back to top

What does a 17th century Dutch painter have in common with the apostle Paul? The two have more in common than one might think. Rembrandt often painted pictures of Paul so Paul obviously had a major impact on his life. In his paintings, he tried to capture the force and emotion of Paul's letters. He also painted other biblical stories as well. While one might have a hard time seeing the relevance, if you open your mind and your spirit you will be pleasantly surprised.

Rembrandt Harmenzoon van Rijn was a seventeenth century Dutch painter. Born in Holland, his completed works were greatly influenced by the Bible and his Protestant faith. In fact, he attempted to capture the force and emotion of the life and letters of Paul in his paintings. We should consider just how Christianity influenced Rembrandt's work. During this period, Dutch painting focused mostly on material themes not spiritual themes. What Rembrandt painted went against the grain of the times so personally this had to be important to him. It probably was not natural to dare to be different at this time but he did it.

Introduction back to top

It is astonishing how often writings on Rembrandt compare him to Shakespeare. This reveals the amount of respect that is given to the 17th-century Dutch painter, and deservedly so. Rembrandt's paintings "typically have a complexity, a richness, that lesser artists seldom even aspire to" (Veith). Particularly groundbreaking from a technical standpoint was his expressive use of light. But also remembered is his uncanny reading of human feelings and reactions. "Like Shakespeare, he seems to have been able to get into the skin of all types of men, and to know how they would behave in any given situation" (Gombrich). This ability is what also makes his paintings of biblical stories so unique. Examples are seen in Rembrandt's paintings of Paul. The influence of the Bible and the Protestant faith on Rembrandt was tremendous. It is clear the life and letters of Paul impacted Rembrandt enough to try and capture the force and emotion of them in his paintings.

Life of Rembrandt back to top

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn was born in Leyden, Holland on July 15, 1606. At age seven, Rembrandt went to Latin School in Leyden. In 1620, he enrolled as a student at Leyden University where he ended up staying only a few months. His passion for painting led him to quit school and devote full time to his art. For three years he served as an apprentice to Jacob van Swanenburgh in Leyden, followed by six more months in Pieter Lastmann's studio in the Breestraat, Amsterdam. It was here that Rembrandt was introduced to the great Italian painters of his day, a group he was both influenced by and who he differed from. In 1625, Rembrandt set up as an independent artist in Leyden where he shared a studio with a friend. This period produced many paintings with biblical themes, including work on St. Paul. Rembrandt left his hometown in 1632 to permanently settle in Amsterdam. It was here that his reputation began to grow rapidly, primarily due to his skill of producing commissioned portraits. The following year Rembrandt fell in love with Saskia van Uylenburch, a miller's daughter, and he married her in 1634. His marriage and family were marred with heartbreak and tragedy. Rembrandt and Saskia lost three young children, and Saskia herself became ill and died in 1642.

During this time, Rembrandt continued to develop his style, as he never settled for imitation of the Italian masters. The same year that Saskia died, he painted the Night Watch, which some see as a revolutionary painting for him. The work contained an unusual depth, expressed in his chiaroscuro style. Chiaroscuro was the emphasis on light and darkness as a means of organization and expression within the picture. His pictures more and more are characterized by emotional honesty and inner restlessness. Rembrandt's nonconformity eventually led to a decline in reputation and opportunity.

His difficulties increased in the 1650s. Commissions were not coming in and debt was growing. During this time another significant woman came into his life, Hendrickje Stoffels. Despite the affection between them, he could not marry her due to a provision in Saskia's will which said a second marriage would require him to repay son Titus the amount of his mother's inheritance. In 1656, he transferred his house to Titus, and an inventory was taken of the house in the Breestraat. 1657-58 saw the auctioning of many of his possessions due to rising debt. Hendrickje and Titus set up an art dealership in 1660, making Rembrandt their employee. But tragedy struck him again as both Hendrickje [1663] and Titus [1668] died in his lifetime. Rembrandt continued to struggle financially the rest of his life and essentially died a pauper in 1669.

Christian Influences on Rembrandt back to top

Given the amount of biblical content in his work, the influence of Christianity on Rembrandt, who was raised a devout Protestant by his mother, deserves to be considered. Merely the painting of Christian subjects does not necessitate an interest in the faith by the painter, but the emotional power of Rembrandt's work reveals a personal concern. E.H. Gombrich writes: "As a devout Protestant, Rembrandt must have read the Bible again and again. He entered the spirit of its episodes, and attempted to visualize exactly what the situation must have been like, and how people would have moved and borne themselves at such a moment" (Gombrich, 315). It is unique that Rembrandt brought his special ability in the art of genre, the depiction of scenes from everyday life purged of the mystically spectacular, to bear in his religious paintings. This fusion of genre with religious mystery made his religious paintings stand out. It showed Rembrandt's concern for the reality of truth, as "the fact was too pregnant with its own meaning to require the addition of rhetoric or splendour" (Newton and Neill, 192).

It is also true that much Dutch painting at the time focused on material rather than spiritual themes. Rembrandt seemed to have the integrity to go against the grain and paint what was personally important to him. Christianity undoubtedly was important to Rembrandt as the spiritual realism of his work reveals. W.A. Visser't Hooft makes an interesting analogy between Rembrandt's Protestantism and Luther's theology of the cross. Luther said that anyone who recognizes God in his glory and majesty must also recognize him in the abasement and igonimy of the cross. There is a sense in which this theology is paralleled in Rembrandt's painting, and it is in this sense that we may speak of Rembrandt's Protestantism. Visser't Hooft writes: "He was Protestant, because he became more and more deeply absorbed in the biblical testimony, because he interpreted the gospel in the light of this very gospel, without calling in the assistance of any classical or humanist ideal, and he did not attempt to force the paradox of the cross into human dimensions" (Hooft,116).

Paul and Rembrandt back to top

Some of the best examples of Rembrandt's spiritual realism are seen in his works on Paul. "St. Paul in Prison" was done by Rembrandt in approximately 1627. This early work reflects Rembrandt's expertise in using chiaroscuro as "the extension of the light and dark accents from tangible to intangible things." Jakob Rosenberg also writes:

Voids as well as solids are emphasized; space gains an expressive life, and becomes an inseparable part of the figures' existence...He seems to have felt that light and dark are magic elements which the painter can employ to veil or to reveal, to create drama and mood, to open the spectator's mind to the unknown depths of vision and feeling (Rosenberg).

This depth of vision and feeling is seen with the deep, thoughtful gaze of the apostle. Paul's passionate concern for the gospel is vividly captured by Rembrandt. The painting reveals Paul's emphasis on the Word of God [as the sword of the Spirit] and his role as an apostle bringing the Word. The use of light and shadow is especially seen in the reflection of the prison bars and the light shining through to illuminate Paul's concern.

The painting of Peter and Paul has been subject to much debate as to whether it is the two apostles or merely philosophers. The face of Paul is strikingly similar to the painting of Paul in prison. Paul also has traditionally been painted with a long face and beard. The round head, whiskers, and garland of curls indicate that the other gentleman is Peter, "since all are symbols which have characterized Peter since the early depictions" (Partsch, 32). The globe is symbolic of the universal scope of Paul's missionary work, and "the extinguished candle, a symbol for the Old Testament, lie in the shadows" (Partsch). The picture reveals Paul as a man of letters and of passionate articulation of the gospel.

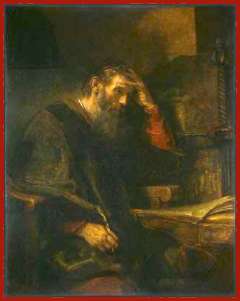

In 1659, Rembrandt finished another painting of the Apostle Paul. It is a peaceful scene of Paul writing letters at his desk. It is interesting to note the contrast between this picture and the exhilarating action of the Baroque paintings of Paul. Rembrandt, instead of emphasizing the action, "portrays Paul as the embodiment of profound meditation" (Goldscheider, 180). A sword, trademark of Paul, leans against the wall. While his face basks in radiant light, the rest of the painting is dark with heavy colors.

In 1661, Rembrandt painted a self-portrait as the apostle Paul. This picture was linked to his series of apostles and evangelists. His head is turned in a diagonal fashion in which he looks right at the beholder. He is perhaps holding the Old Testament, and the sword symbolic of Paul lays at his side. Paul's stare is questioning, doubting. Susanna Partsch writes, "There is nothing apostolic or indeed lordly about this face; it is the face of a man of experience who is sceptical about the future" (Partsch, 187). This was painted in a time where Rembrandt's own life was filled with hardships, and it seems that this reflects his mood at the time. It is interesting that he identifies himself with Paul, no stranger to dark times himself.

Rembrandt's legacy continues to impact the lives of people today. His own life was impacted by the legacy of Paul and the gospel he preached.

Self-Portraits back to top

Click an image to view a larger version.

1640

1661

1669

Bibliography back to top

- Bredius, Abraham. The Complete Edition of the Paintings. Revised by H. Gerson. London: Phaidon Press, 3rd edition 1969.

- Cheney, Sheldon. A World History of Art. New York: Viking Press, 1964.

- Clark, Kenneth. An Introduction to Rembrandt. New York: Harper & Row, 1978.

- ______________. Rembrandt and the Italian Renaissance. London: John Murray Press, 1966.

- Goldscheider, Ludwig. Rembrandt: Paintings, Drawings and Etchings. New York: Phaidon, 1964.

- Gombrich, E.H. The Story of Art. New York: Phaidon, 1956.

- Knackfuss, Herman. Rembrandt. Translated by Campbell Dodson. New York: Lemcke & Buechner, 1899.

- Newton, Eric and William Neill. 2000 Years of Christian Art. New York: Harper & Row, 1986.

- Partsch, Susanna. Rembrandt. London: Weidenfield & Nicolson, 1991.

- Rosenberg, Jakob. Rembrandt. London: Phaidon Press, 1964.

- Veith, Gene Edward, Jr. State of the Arts: From Bezalel to Mapplethorpe. Wheaton: Crossway Books, 1991.

- Visser 't Hooft, W.A. Rembrandt and the Gospel. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1957.

- White, Christopher. Rembrandt and His World. London: Thames & Hudson, 1966.

- Zumthor, Paul. Daily Life in Rembrandt's Holland. London: Weidenfield & Nicolson, 1962.

Links back to top